Bank on Aegean Subjects

DBAS - @egeanLab

DBAS-TWC Textile work areas in Bronze Age Crete

Maria Emanuela Alberti

Cristian Faralli (technical support)

(work in progress)

Textile database

Archaeological indicators, typology and interpretation

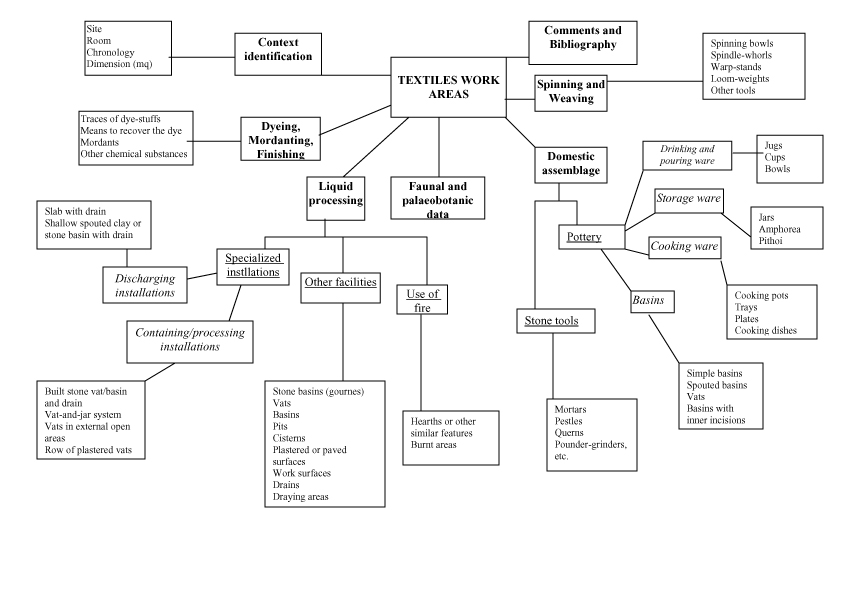

- Presentation: aims and problemsThis Data Base has been built during the work for my Ph.D. Diss. on the evidence for textile fibre processing in BA Crete at the University of Udine, Italy (Gli impianti per la lavorazione delle fibre tessili nell'Egeo dell'età del bronzo, con particolare attenzione alla ceramica d'uso industriale, Udine 2005). It is still in progress, since it is changing with the progressing of my research.Each step of textile production (fibre harvest, combing, washing fibres, dyeing, mordanting, spinning, weaving, finishing) has its own indicators, but not every step is equally documented in Minoan record. The present work aims not only to review the available pieces of evidence, but also to propose a preliminary typological classification and a first differentiation between various scales of production. The sample used for the analysis is quite small and mainly dated to the Neopalatial period: this is only a first attempt.

- Aim of the work is to give a preliminary picture of the relevant characteristics of Minoan textile work areas and the main attested archaeological indicators of textile production. The identification of textile work areas is not an easy task, since elements referring to each phase of fibre processing should be taken into account. In recent years, many scholars suggested, on a general level, a selection of indicators and some suitable interpretative grids (Barber 1991; Monaghan 2000; for Roman times, see also Uscatescu 1994, 164-5, tab. 1-2). For the Aegean, see the recent review in Evely 1999-2003, 485-511, fig. 200-204. See also Carington Smith 1975; Tzachili 1997; Militello 2001. For the individuation of a work area on a general level, see Evely 1988; Tournavitou 1988; Vidale 1992, 114-1116. When examining Minoan work areas, we should bear in mind that most of the contexts are multi-purpose, dedicated to various domestic activities and/or to food-stuffs processing. A large part of the archaeological assemblage is, consequently, multi-purpose, potentially used in many productive cycles: querns, pounder-grinders, mortars, pestels, cooking pots, simple basins, not to consider facilities like work-benches or paved floors. There are also some more specialized equipments, as spindle-whorls and loom-weights for textile making, or shallow spouted press-beds for olive pressing. The coexistence of indicators of various activities in the same areas is a generalized condition, thus suggesting a real mixed use of spaces in antiquity. In this context, the documented textile activities are only part of the productive processes carried on the examined work areas.

-

Identification of Minoan textile work areas: choosing the archaeological indicatorsAs it has been recalled, the identification of a textile work areas depends on a series of indicators. As stated by Doniert Evely, «Combination improve the chances» (Evely 1993-2000, 550-1. See also Alberti fothcoming a and c). Therefore, for each context, they have to be mapped all the possible indicators related to each step of production, from fibre harvest to finishing. However, the combination could really tell us something, only if two different parameters are considered: the functional specialization on one hand, and the quantity of the attestations, on the other. In this way, the grid will express both the specialization and the intensity and scale of the working activities.

- Site identification.

First of all, for each context should be given the fundamental data: name, chronology, exact context (if a room or a group of rooms, and not a whole structure, are concerned), bibliography and particular notes. - Functional specialization.

Secondarily, for each context the presence of the following indicators of functional specialization has to be verified:- dye-stuffs;

- mordents or other chemical substances;

- discharging installations (slab with drain, shallow spouted clay or stone basin with drain);

- "serial" particular installations for liquid processing (row of vats);

- other particular installations for liquid processing (i.e. stone built vat and drain);

- domestic equipment for large-scale liquid processing (vat-and jar system);

- domestic equipment for medium and small scale liquid processing (vats, basins, drains, paved or plastered areas);

- detail of the basins (real vats with bottom spout, spouted basins, simple basins, stone basins);

- typical domestic assemblage (cooking and storage vessels, stone tools, hearths, etc.);

- textile tools proper (spindles, spinning bowls, spindle-whorls, loom-weights);

- other.

- Quantity, intensity and scale.

We should also verify some quantitative parameters, such as:- complexity and surface of the considered buildings;

- number of the productive areas;

- number of the particular or large-scale equipment for liquid processing;

- number of the domestic small or medium scale equipment for liquid processing;

- number of the textile tools.

- Site identification.

- [downloadable image

PDF (14.24 KB) ]

-

Analysis

On the ground of such a Data Base, an interpretation grid can be built, with attention to the two parameters of specialization and intensity and scale of the working activities. The various combinations of indicators will point to different patterns of evidence, characterising different groups of sites. Each of this group would represent productive units of different specialization, dimension and complexity, from household to "large-scale" production. Such a picture can be finally related to the Linear B evidence, in order to compare the assessed archaeological evidence with the administrative record (Alberti 2005 and forthcoming c).

References:

- ALBERTI, M.E. (2005), Problemi di organizzazione produttiva a Creta in età neopalaziale, con un'appendice sull'età micenea. Studio in onore di Federico Halbherr, svolto per conto della Provincia Autonoma di Trento presso la Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene nel corso del 2005.

- ALBERTI, M.E. (forthcoming a), "Washing and Dyeing Installations of the Ancient Mediterranean: towards a Definition from Roman Times back to Minoan Crete", in B. BURKE, C. GILLIS, M.L. NOSCH, U. MANNERING (eds.), Ancient Textiles, Production, Crafts and Society. Proceedings of the Conference held in Lund (Sweden) and Copenhagen (Denmark) in March 2003, forthcoming.

- ALBERTI, M.E. (forthcoming b), "Washing and Liquid Processing in Minoan Households: Facilities, Tools and Some Reflections on the Scale of Production", in K. GLOWACKI, N. VOGEIKOFF-BROGAN (eds.), STEGA. The Archaeology of Houses and Households in ancient Crete from the Neolithic Period through the Roman Era, Proceedings of the Internatioanl Colloquium held in Ierapetra 26-28 May 2005 (forthcoming in the Hesperia Supplement Series).

- Alberti, M.E. (forthcoming c), "Textile Industry Indicators in Minoan Work Areas: Problems of Typology and Interpretation", in C. Alfaro, L. Karali (eds.), Textiles and dyes in the Ancient Mediterranean World, 2nd International Symposium, Athens 24-26 November 2005 (forthcoming for the University of Valencia Press).

- BARBER, E.J.W. (1991), Prehistoric Textiles. The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, Princeton, New Jersey.

- CARINGTON SMITH, J. (1975), Spinning, Weaving, and Textile Manufacture in Prehistoric Greece (Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tasmania, Hobart).

- EVELY, R.D.G. (1988), "Minoan Craftsmen: Problems of Recognition and Definition", Problems, 397-416.

- EVELY, R.D.G. (1993 - 2000), Minoan Crafts: Tools and Techniques. An Introduction, voll. 1-2, SIMA 92; vol. 1, Göteborg 1993; vol. 2, Jonsered 2000.

- MILITELLO, P. (2001), "Spinning and Weaving in Festos and Aghia Triada from Neolithic through Geometric Ages", in Proceedings of the 9th International Congress of Cretan Studies/ Pepragmena Q Dieqnouz Krhtologikon Sunedriou, Elounta, 1/6 Oktwbriou 2001, 55 (abstract).

- MONAGHAN, M. (2000), "Dyeing Establishments in Classical and Hellenistic Greece", in D. CARDON, M. FEUGÈRE, Archéologie des textiles des origines au Ve siècle. Actes du colloque de Lattes, octobre 1999, Monographies instrumentum 14, Montagnac, 167-172.

- Problems - E.B. FRENCH, K.A. WARDLE (eds.) (1988), Problems in Greek Prehistory. Papers Presented at the Centenary Conference of the British School of Archaeology at Athens, Manchester April 1986, Bristol.

- TOURNAVITOU, I. (1988), "Towards an Identification of a Workshop Space", Problems, 447-468.

- TZACHILI, I. (1997), Ujantikh ujantrez kai sto Proistroiko Aigaio 2000/1000 p.C., Hrakleio

- USCATESCU, A. (1994), Fullonicae y tinctoriae en el mundo romano, Barcelona.

- VIDALE, M. (1992), Produzione Artigianale Protostorica. Etnoarcheologia e Archeologia. Saltuarie del laboratorio del Piovego 4, Padova.